22 November 2025

Gabrielle Chanel, known as “Coco” Chanel, was a revolutionary French fashion designer and businesswoman, the founder of the iconic House of CHANEL. She is credited with popularizing a casual chic style and is the only fashion designer listed on Time magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century. Here, the story of her rise and the legend that will live on forever.

In 1910, at 21 Rue Cambon, Coco opened her first boutique, a hat shop, called Chanel Modes. She was 27. Financed by her great love, Arthur “Boy” Capel, because he truly believed in her gift. At the time, women did not have the right to open their own bank account or start their own business. Boy’s support allowed Coco to pursue her dream, but it didn’t take long for her to pay him back everything he gave her.

The hat shop serviced well-known actresses and high society ladies who were intrigued by her pared down and simple designs. It also gave her the opportunity to showcase the clothing she made. Coco was the original influencer. She would dress in her own creations – trousers and loose fitting cardigans – and soon others were inspired to dress as she did. She was her own muse and model.

In 1913 she opened a boutique in Deauville. In 1915 she opened a boutique in Biarritz, where she designed her first Haute Couture collection and employed 300 people. In 1918 (at the end of WW1) she relocated back to Paris. This time at a new 6 storey building located at 31 Rue Cambon. She set up this location to include a boutique, salons, workshops and a private apartment – a layout that is still intact to this day as the CHANEL Headquarters.

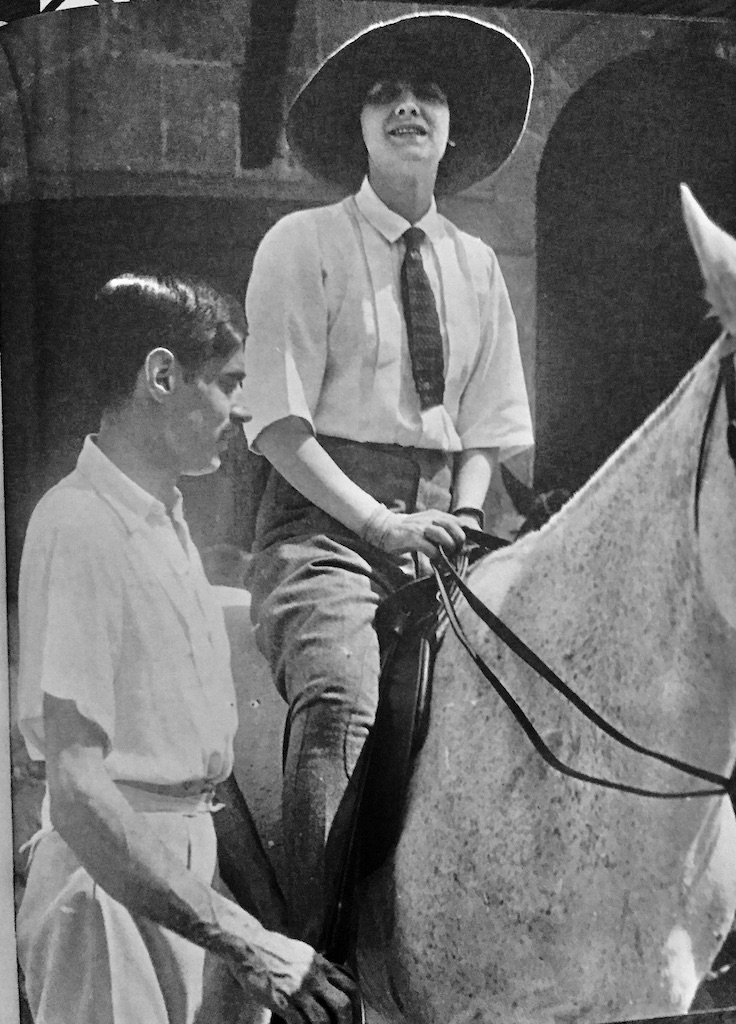

Gabrielle Chanel in front of her store

Gabrielle Chanel and Boy Capel

Arthur “Boy” Capel died in a tragic car accident on December 22, 1919. In Chanel’s own words: “His death was a terrible blow to me. In losing Capel, I lost everything.” But Coco was a survivor. She grieved and then proceeded to create some of her most iconic creations.

Everyone knows CHANEL N°5 – the fragrance has been popular since its creation. Gabrielle wanted to create a signature scent that was different from the scents of the day. They were mostly single-note floral scents. She craved something more multi-faceted, composed of variously proportioned layers of dynamic scents. Something that could reflect the identity of the modern woman. Just like her clothing did. In 1921, Coco entrusted Ernest Beaux to bring her vision to life. He created 10 variations, working with over 80 notes and incorporating aldehydes, which was very rare at the time. As the legend goes, Coco, being superstitious as she was, selected the fifth sample, as it was her lucky number, and chose to keep the name N°5 so it would continue to bring her luck. As she did with her fashion, Coco was the influencer for her scent. She would wear it herself, give samples to her close friends, and spray it in her boutique before making it available to the masses. It became a success instantly. Housed in a clear glass bottle – modern, clean and simple – N°5 began distribution in 1924 once “Parfumes Chanel” was officially incorporated. Gabrielle partnered with Pierre and Paul Wertheimer, who managed the production and distribution of the perfume. The Wertheimers received 70%, Rheophile Bader (the broker of the deal and founder of the Galeries Lafayette) received 20% and Gabrielle Chanel received 10%.

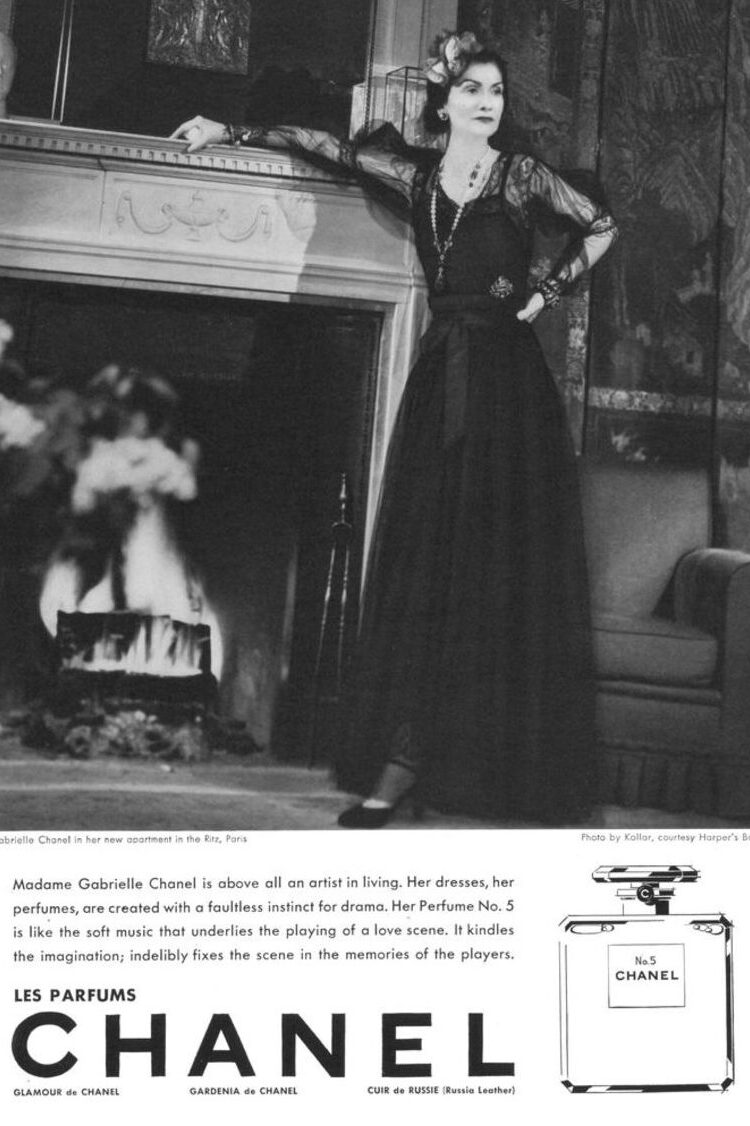

The original CHANEL N°5 bottle

An original CHANEL N°5 ad

Illustration by Sem

The CHANEL tweed suit has officially existed for 100 years. In 1924, Coco began a decade-long relationship with Hugh Richard Arthur Grosvenor, the 2nd Duke of Westminster. As with her previous relationships, Coco borrowed her lover’s clothing and in this case, it was a tweed jacket. Originating in Scotland, tweed was primarily used for men’s sportswear jackets for its thickness and durability. But of course, Coco became fond of the garment and reshaped it to suit a more feminine silhouette. She also worked closely with a tweed manufacturer in Scotland to fashion the fabric into something more comfortable and lightweight for everyday wear. She debuted her original design in 1925 during a showing at 31 Rue Cambon – a boxy jacket, fitted skirt, interlocking C’s on the buttons and a chain sewn into the hem of the jacket to hold it in place. Another instant classic that would symbolize a woman’s need for freedom while remaining chic.

A CHANEL design

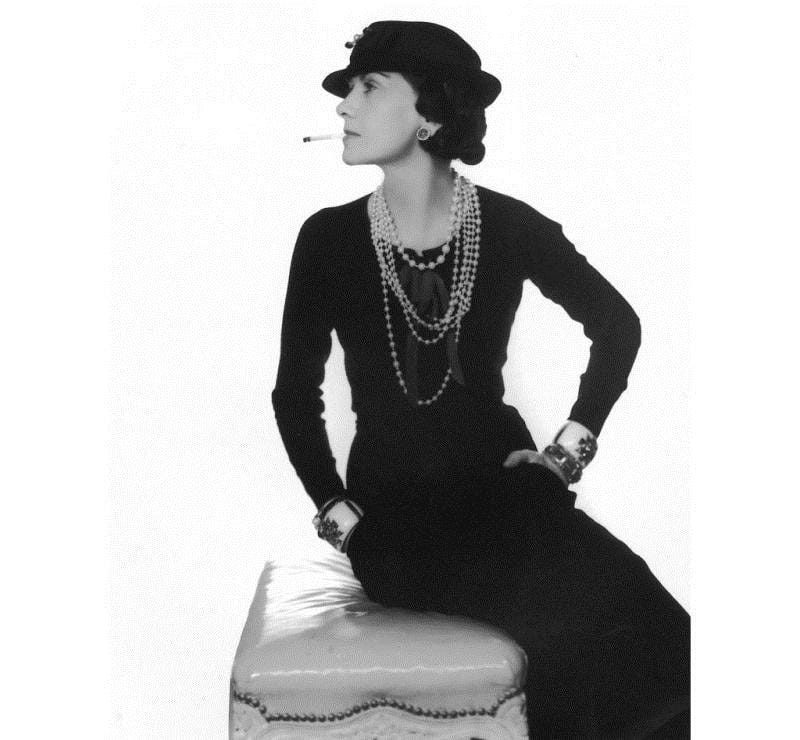

Gabrielle Chanel wearing one of her own designs

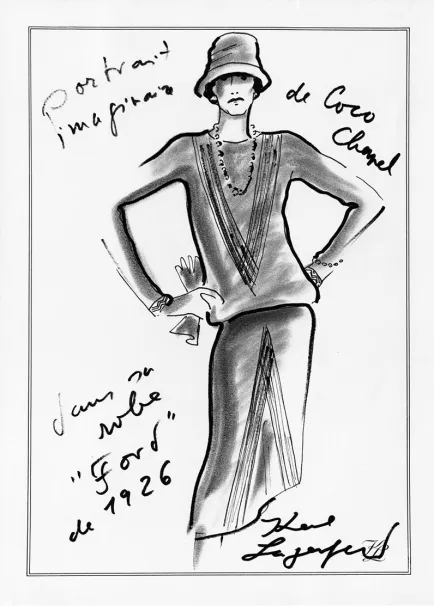

Coco didn’t invent the Little Black Dress – or LBD as it came to be known – but she did popularize it. At this time, black was not a colour considered to be worn unless one was in mourning. Gabrielle’s views were different. She saw black as modern and chic, choosing to wear it as early as the 1910’s. However, 1926 would become the year historically binding the colour with CHANEL. Referred to by Vogue as “Chanel’s Ford” in 1926 due to its mass appeal (just like the American car), the magazine called her design “the frock that all the world will wear”. Forever and ever. The LBD has never gone out of style and is still an essential part of each CHANEL collection.

CHANEL wearing one of her iconic black dresses

An illustration by Karl Lagerfeld

A CHANEL design

The House of Chanel thrived throughout the 20’s and 30’s. But in 1939, with the onset of WW2, Gabrielle closed the doors to her couture house. The only item still being produced and sold was CHANEL N°5. During this time, there was much dispute between Chanel and the Werthiemer’s over their agreement as Coco felt she was not receiving a fair share of the success.

Coco took up residence at the Hotel Ritz and would live there during the duration of the war. Much is said about Coco’s connections and actions during the war, much of it unproven. She was never charged as a collaborator, possibly due to the intervention of her close acquaintance, Winston Churchill. However, her reputation was affected and at the end of the war – in 1945 – she moved to Switzerland where she remained until 1953.

In 1948 Pierre Werthiemer visited Chanel in Switzerland to re-negotiated the terms of their agreement. They settled on a substantial cash payment to Chanel reflecting profits of CHANEL N°5 sales during the war, a 2% running royalty from the continued sales of the perfume, and a monthly stipend that covered all of Coco’s living expenses. In return, she turned over full rights to her name “Coco Chanel” to “Parfumes Chanel”.

In 1953, Coco felt it was time to return to Paris. Why? When asked this question, her response was, “Because I was dying of boredom.” She was 71. Designers like Christian Dior and Cristobal Balenciaga were gaining popularity, creating dresses with cinched waists and full skirts. Coco was ready to rebel. Again. She wanted to modernize the CHANEL aesthetic, to again design for women who lived full, chic lives.

To relaunch, she needed financing and so she went to Pierre Werthiemer. He agreed and in 1954, “Parfumes Chanel” became “Chanel Societe Anonyme”. The Werthiemers had full ownership but Gabrielle Chanel remained director and retained complete control over all design aspects.

Her comeback collection was shown at 31 Rue Cambon on February 5, 1954. She had worked tirelessly for almost a year, preparing with endless fittings, scrutinizing every detail. The collection was met with mixed reviews – the French hated it, the Americans loved it. Life magazine said, “At 71 years of age, Gabrielle Chanel has created more than fashion, she has created a revolution.” With stars like Marlene Dietrich, Romy Schneider and Elizabeth Taylor dressing in CHANEL, she was back at the forefront of fashion. In 1957, she received the Neiman Marcus Award for “Distinguished Service in the Field of Fashion”. Her undeniable perseverance was at work, leading her again to create more of her most timeless designs. And the French eventually came around.

Chanel at 31 Rue Cambon

Chanel fitting Romy Schneider

“A CHANEL suit is made for a woman who moves.” said Coco Chanel. The inspiration came to Coco while on holiday in Austria. The uniforms worn by the staff at a hotel intrigued her. Without shoulder pads and collarless, the jacket silhouette was freeing. Coco added her feminine touches – braided trim, spectacular buttons and pockets. It became a refined version of her earlier designs. Her collections included various options, with matching skirts and blouses, in endless fabric choices – for day or night. Lighter fabrics, taking on a more cardigan-like fit, were ideal for daytime while shimming or silky fabrics could be worn for dressier occasions. While the beauty of the CHANEL suit is its apparent simplicity, the detailed process of crafting the suit is anything but simple. Coco was a true couturière and perfectionist – the cut, the panels, the stitching, the lining, the braiding, the buttonholes were all designed in a specific way to allow for comfort and ease of movement without distributing the flow of the pieces. One of the most special elements was the chain sewn into the hem of the jacket to ensure that the jacket would always fall into place. With Hollywood’s most-loved actresses all wearing CHANEL suits, the look became a staple in women’s fashion, known as “the CHANEL style”.

“I tired of holding my bags in my hand and losing them, so I added a strap and wore them over my shoulder.” And a classic was born. Like all of Coco’s iconic designs, her handbag was a creation of functional elegance with design elements drawing inspiration from her past. With a quilted diamond pattern stitched into the leather, reminiscent of jockeys riding jackets or possibly the stained glass windows at Aubazine.

A double chain shoulder strap, similar to the chains the nuns would wear around their waist at Aubazine. A burgundy lined interior with a zippered compartment, the same colour as her convent uniform. The zippered compartment was said to be for concealing her love letters. At the orphanage, young Gabrielle would hide pages from romance novels amongst her things. A pocket on the outside backside and a turn lock closure on the front, now called the “Mademoiselle Lock”, for convenience. These are all now well known design features of an everlasting “it” bag, but at the time they were revolutionary.

Named the 2.55 after its release date – February 1955 – this bag is not to be confused with the Classic Flap. The Classic Flap was created later (in the image of the 2.55) by Karl Lagerfeld. Its most notable difference is the leather woven through the chain strap and the interlocking CC turn lock closure.

“We leave in the morning with a beige and black, we lunch with beige and black, we go to a cocktail party with the beige and black. We are dressed from morning to night.” These are the words Coco Chanel used to describe her latest design, presenting the two-tone slingbacks in 1957. A shoe designed for practicality, from day to night, with any outfit. She worked with the shoemaker Massaro to design and produce the shoe – beige leather to match her skin tone and elongate the leg, with a black almond toe to make the foot appear slimmer. They are said to be inspired by a pair of sandals worn by Serge Lifar, a dancer and close friend of Coco’s. The shoes gained popularity for their elegant ease. With a 5 cm heel, they were comfortable. With an elastic strap instead of a buckle, there was no fuse. They became known as “the new Cinderella slipper”. Another innovation by Coco that has stood the test of the time.

Coco Chanel continued to work on her collections until the day she died. Her work was always her true love, it was the life she had created for herself.

She died on January 10, 1971 in her bed in her suite at the Ritz Paris. She was 87. Her last words to her maid were, “You see, this is how you die.” Her final collection – Spring 1971 – was presented two weeks after her death.

Photo by Douglas Kirkland, 1962