23 August 2025

Coco Chanel introduced the tweed suit during the 1920s. Her design challenged the era’s norms by replacing stiff corsets and restrictive cuts with ease, mobility, and polish. It wasn’t just about appearance. She built the suit with a purpose: to support women living active lives. Behind this shift in style were key influences drawn from her personal relationships and surroundings.

While vacationing in Scotland with the Duke of Westminster, Chanel discovered traditional tweed. At the time, the fabric was used mainly in British men’s sportswear and Chanel often wore the Duke’s jackets and vests herself. In addition to the material, their shape would also influence her suit design.

She saw potential in tweeds durability, texture, and warmth. Rather than copy these garments, she reimagined them for women. She sourced fabric directly from Scottish mills, requesting custom weaves in lighter weights and more subtle finishes. These adjustments allowed the material to drape rather than stiffen. It kept its texture but softened in tone. The suit’s look began here—with raw fabric reworked to match her vision of strength and freedom.

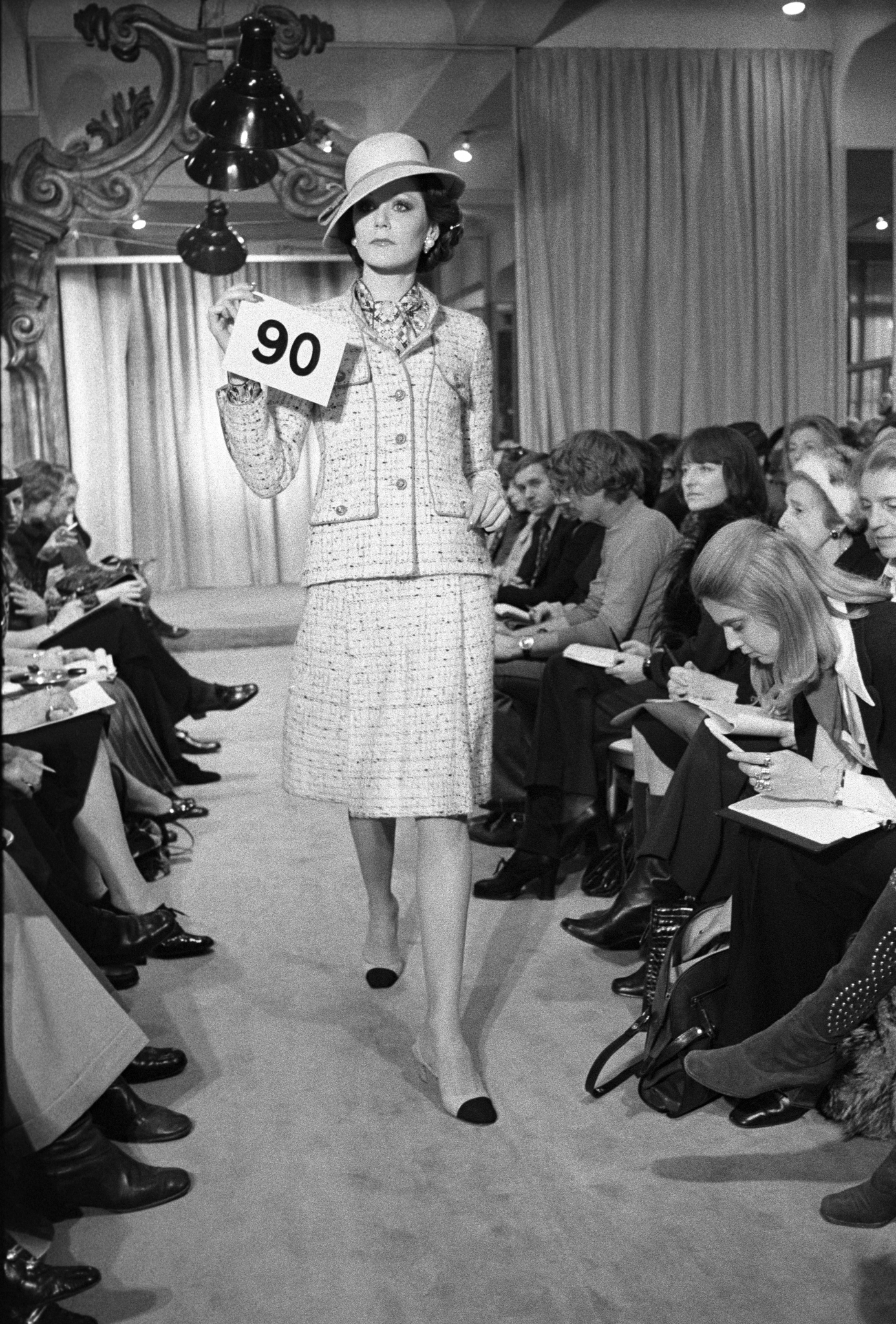

She replaced overly structured women’s fashion with lines that echoed men’s sports coats—straight, clean, and easy to wear. Her jackets lacked darts and padding, relying instead on the nature of the fabric and precise cuts. This approach removed decoration for its own sake. Instead, she placed emphasis on construction, movement, and balance.

Chanel frequently borrowed from men’s wardrobes and the influence of military uniforms also played a role. Chanel appreciated their order and structure. You can see this reflected in the four-pocket layout of many jackets, as well as the straight silhouettes.

The suit arrived at a time when women’s roles were changing. Chanel did not design with fantasy in mind. She designed for reality—one in which women needed clothing to carry them from meetings to dinners without discomfort or complication. The tweed suit allowed that shift to take place without losing polish.

Chanel believed clothes should serve the body, not restrict it. Every detail of the suit supports that idea. Buttons close the jacket cleanly without strain. Sleeves follow the arm’s natural bend, making movement easier. Lightweight linings let the fabric move with the body. The signature chain sewn into the hem helps maintain shape without using stiffeners. By replacing decoration with structure, she created a new visual language. This style did not rely on ornament. It drew strength from simplicity.

Color choices often drew from nature and city life. She used stone, moss, sand, and sky tones to anchor the suit in real environments. This approach gave the suit a calm confidence rather than flash. It could fit into daily life while standing out through quiet precision. Moreover, the visual weight of the tweed itself balanced the minimal shape. The result was elegant without being fragile.

Through decades of change, the core of the suit has held steady. The fabric still signals tradition, but the cuts reflect modern life. Karl Lagerfeld introduced variations in length, color, and layering. Virginie Viard continued to update the silhouette for new generations, but the roots remained visible. Shorts, trousers, and metallic threads have appeared in recent collections. Yet the emphasis on ease and shape has stayed. This evolution shows that a strong foundation allows for steady growth without loss of identity. What will Matthieu Blazy do?

Chanel’s tweed suit tells a story of adaptation. It started with a woman borrowing from men’s clothing and asking more from materials. It became a statement of balance between style and function. The design responded to real life, not fantasy. That is why it has lasted.

Each element of the suit serves a clear role. You can trace every thread to choices grounded in experience, need, and intention. Nothing is added without reason. This principle—form following purpose—remains the most powerful influence behind Chanel’s signature suit. It stands today not just as fashion, but as a clear idea made wearable. And it continues to speak—in form, in fabric, in quiet authority.