31 January 2026

At the heart of CHANEL Haute Couture lies a network of highly specialized ateliers, concentrated primarily at 31 Rue Cambon in Paris. These workrooms are not simply production spaces; they are repositories of institutional memory, technical knowledge, and creative continuity. Within them, generations of artisans have refined skills that cannot be taught quickly, mechanized, or outsourced. They embody the highest standard of luxury and excellence. The couture ateliers are traditionally divided into two principal domains:

The tailleur atelier is responsible for structured garments – most notably the iconic CHANEL jacket, suits, coats, and tailored dresses. This workshop embodies Gabrielle Chanel’s pursuit of functional elegance. Every tailored piece begins with an internal architecture that determines how the garment will move, fall, and age. Work here involves:

The CHANEL jacket, often considered the technical backbone of the House, can take months to perfect. It is assembled almost entirely by hand, with components built separately and then united through careful stitching. This modular construction allows for flexibility and comfort – an innovation Coco Chanel pioneered to counter the rigidity of early 20th-century tailoring. Each jacket is fitted repeatedly on the client, ensuring that it molds to posture, movement, and personal habits. Over time, a couture jacket becomes almost biometric, shaped by the wearer’s body.

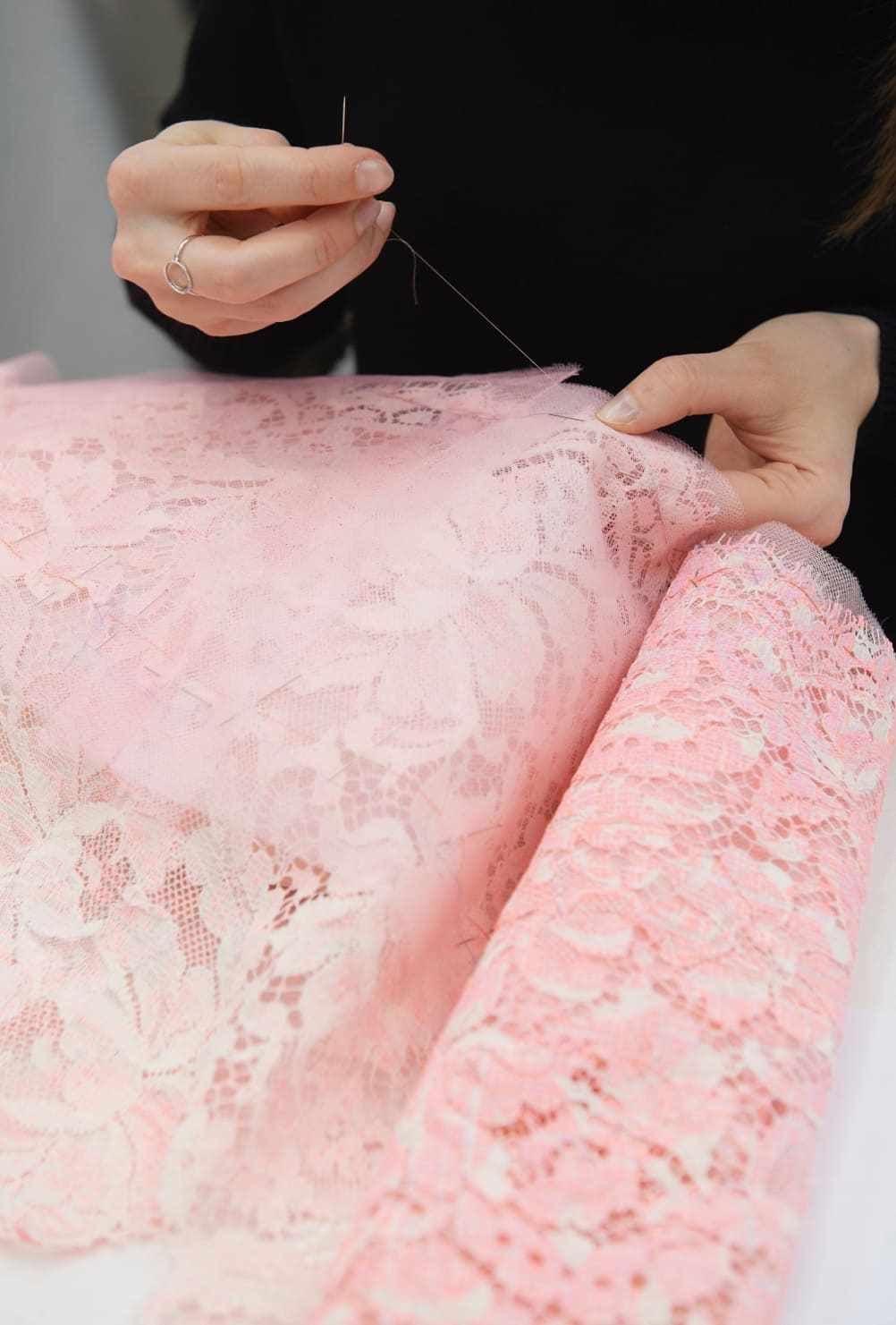

The flou atelier specializes in soft, draped, and fluid garments – gowns, blouses, chiffon dresses, tulle skirts, and feather-light evening wear. “Flou” refers to garments that are constructed through draping rather than rigid patterning. Here, fabric is sculpted directly on mannequins or live models, pinned, pleated, and reshaped by hand. Techniques include:

A couture gown in flou often passes through dozens of iterations before finalization. Some dresses are built entirely on the form, with no initial paper pattern. The garment evolves through dialogue between fabric, artisan, and designer. This atelier preserves a tradition rooted in haute couture’s origins, when garments were literally “sculpted” rather than manufactured.

There is a third, smaller atelier named “galon” which translates to “braid”. A one of a kind atelier, it is strictly dedicated to the production of the iconic CHANEL braiding. A CHANEL code instantly recognizable on the edges and as trim on the CHANEL jacket.

Spring/Summer 2017

Cecil Beaton, Vogue

Beyond its in-house ateliers, CHANEL sustains an ecosystem of independent craft houses – collectively known as the Métiers d’Art – which provide specialized techniques essential to couture production. Many of these workshops were acquired or supported by CHANEL to prevent their disappearance. Key contributors include:

Each couture garment may pass through multiple Métiers d’Art houses to achieve the final piece. This collaborative process transforms a sketch into a composite work of art, made by dozens of hands.

Importantly, CHANEL’s investment in these ateliers is not purely commercial. It reflects a long-term cultural commitment to sustaining endangered forms of craftsmanship in an era of industrial production. For more information, read: Inside CHANEL’s Métiers d’Art: Celebrating Craftsmanship

Fall/Winter 2022

Fall/Winter 2016

The creation of a CHANEL couture garment follows a precise, multi-stage journey that can span six months or more.

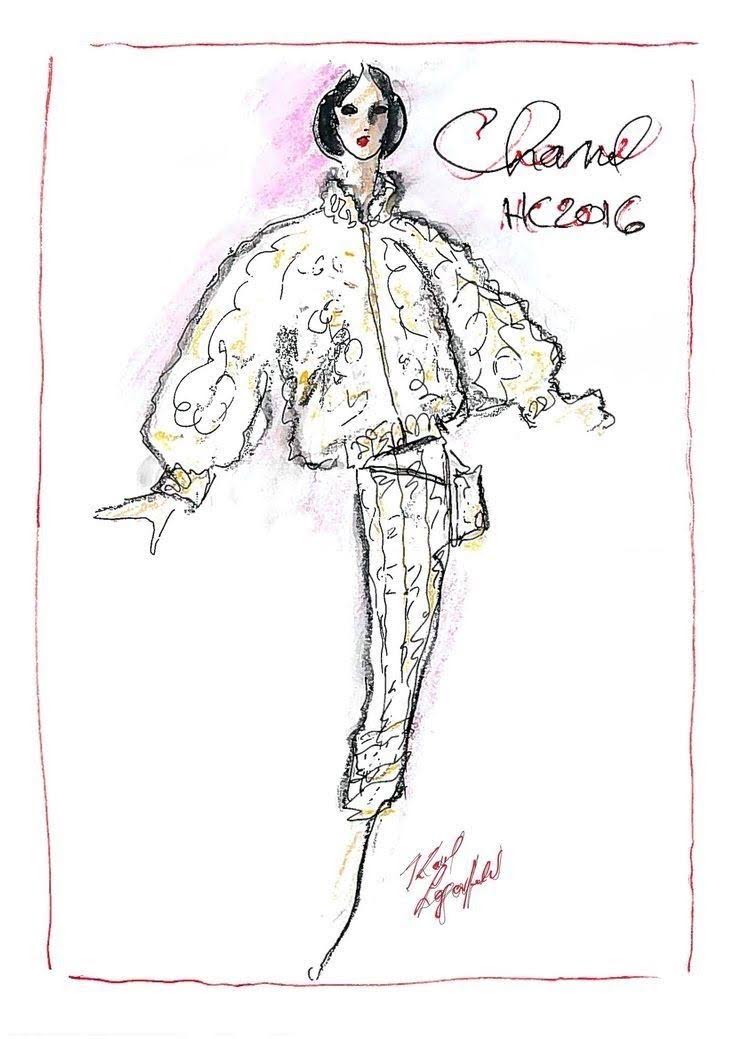

The process begins with the creative direction team developing thematic concepts, silhouettes, and material explorations. Archival references, art, literature, and craftsmanship traditions often guide this phase. Initial sketches are refined into technical drawings that specify structure, fabric, and embellishment.

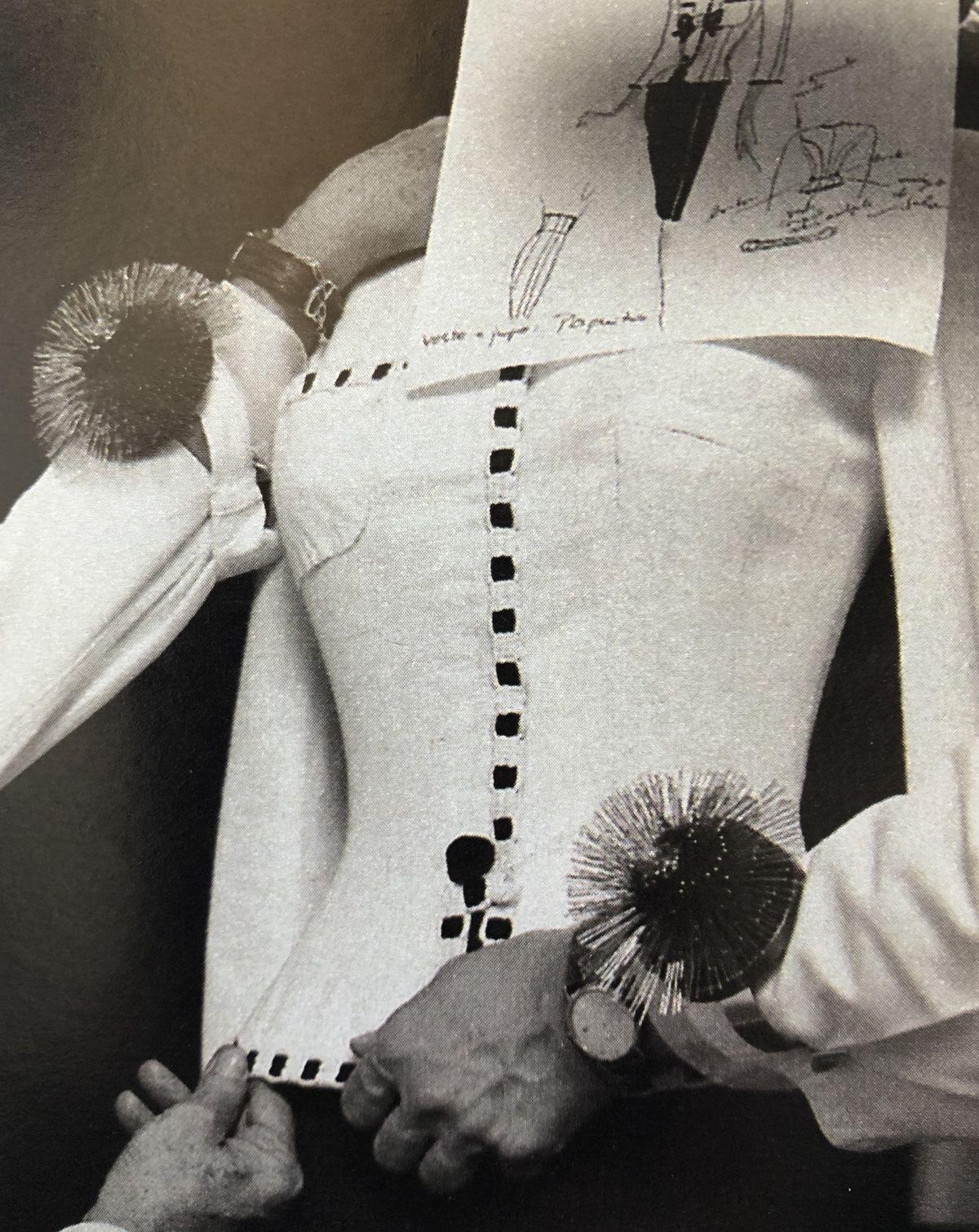

Before fabric is ever cut, each design is translated into a toile – a prototype made from cotton muslin. This stage allows artisans to:

Spring/Summer 2016

Spring/Summer 1995

Couture fabrics are often custom-developed. Tweeds may be woven specifically for one design. Silks, tulles, and organzas are sourced in limited quantities and sometimes hand-dyed. Some materials are pre-treated, softened, reinforced, or embroidered before cutting begins. This preparation alone can take weeks.

Couture garments are not assembled on production lines. Artisans are responsible for major sections of a piece from start to finish. Construction includes:

Custom Design

Fall/Winter 2023

Once the basic structure is established, embellishment begins. Embroidery is applied after initial fittings, then reintegrated into the garment. Beads, sequins, feathers, pearls, and metallic threads are sewn individually. Some dresses contain tens of thousands of elements, each placed by hand.

Clients undergo multiple private fittings. Garments are adjusted to millimeter precision. Even posture and walking style are considered. The final stage includes: lining installation, hand-finished hems and label application. Only when perfection is achieved is the garment considered complete.

Fall/Winter2025

Spring/Summer 2026

One of couture’s greatest challenges today is the transmission of skills. Many techniques used in CHANEL’s ateliers cannot be learned through manuals; they require years of apprenticeship. Senior artisans mentor younger workers, passing on tacit knowledge – how to judge tension in a stitch, how to balance fabric weight, how to correct asymmetry without altering design., etc.

This oral and practical tradition ensures continuity between Coco Chanel’s era and the present. Without couture, much of this knowledge would disappear.

In contemporary fashion, where speed and scalability dominate, CHANEL’s couture ateliers represent a counter-model: slow, deliberate, human-centered production. Their importance lies in several dimensions:

Cultural Value: They preserve rare techniques that belong to fashion history.

Creative Value: They allow designers to experiment beyond industrial constraints.

Educational Value: They train future generations of artisans.

The ateliers of CHANEL are not museums. They are active, evolving spaces where tradition and innovation intersect daily. New materials, digital patterning, and contemporary aesthetics are integrated into centuries-old techniques. This dynamic balance ensures that couture remains alive rather than nostalgic.

Spring/Summer 2019

Spring/Summer 2006

One of couture’s ongoing dialogues is the balance between wearable elegance and avant-garde exploration. Chanel historically found harmony here: pieces that are rooted in everyday life yet elevated to artistic realms. Gabrielle Chanel’s original vision – clothes that respect women’s lives while elevating them through craftsmanship – continues to guide every stitch.

Modern couture collections often amplify this duality. Under creative leadership, recent presentations have blended artful innovations with pieces that, albeit luxurious and bespoke, could be imagined in the context of a real wardrobe. As Matthieu Blazy has said, “Couture doesn’t need to be heavy. It doesn’t need to be big. It’s something about the making, how it falls on the body.”

The essential question – Can couture be both practical and artful? – finds no single answer at CHANEL. Rather, the House continues to treat couture as a spectrum, where wearable sophistication and creative boldness coexist, each enriching the other.

Spring/Summer 2025

Spring/Summer 2026

CHANEL Couture is more than a fashion category; it’s a philosophy. From Gabrielle Chanel’s early innovations to today’s couture ateliers in Paris, couture remains at the heart of the House’s identity- a testament to craftsmanship, creative freedom, and cultural significance.

Its value lies not only in handmade masterpieces, but in what they represent: a bridge between tradition and innovation, between practical elegance and unabashed fantasy. As both a creative engine and a symbol of sartorial excellence, CHANEL Couture continues to shape how we understand couture as an art form that remains undeniably relevant in modern fashion.

Fall/Winter 1985

Fall/Winter 2021